Marietta

ABOUT THE ROUTE

ABOUT THE ROUTE

Veterans of the American Revolution laid out the town of Marietta, respecting grand Adena and Hopewell remains: the cemetery centers on a beautiful mound and ring; the town’s library sits on one of three distinctive rectangular platform mounds. A broad avenue, now a park, follows an ancient graded way to the riverbank. A thriving downtown, plus beautiful residential and historic districts and some fine restaurants, make this a rewarding destination. The surrounding area is full of natural beauty and history.

Several attractive routes from Cincinnati, Chillicothe, or Columbus, lead through Athens to Marietta (see the Athens and Hocking Valley itinerary). From Athens, use US 50, or the somewhat more scenic State Route 550 farther north, to reach Marietta.

Marietta is a well-preserved river town, with many layers of history. When the veterans of the “Ohio Company” arrived with their families in 1788, the huge geometric earthworks were already 1500 or more years old. Several are still well preserved, and it is possible to take them all in via a leisurely walk or drive among beautiful houses, churches, and public buildings. Two excellent museums (Campus Martius and Ohio River) tell the stories of the town’s origins and settlers, and river transport. Trolley and steamboat tours, and a huge festival every September, highlight Marietta’s distinguished history and architecture.

A park frames views of the Ohio and Muskingum River confluence, in downtown Marietta.

HISTORY OF THE EARTHWORKS AND THE TOWN

HISTORY OF THE EARTHWORKS AND THE TOWN

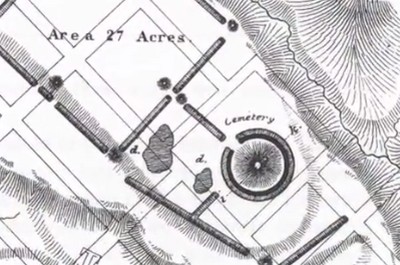

Here, where the Muskingum River joins the Ohio, stood the easternmost of Ohio’s monumental, ancient earthwork complexes. Its unusual plan included a ringed burial mound, two large rectangular enclosures, a set of platform mounds, and a wide graded way down to the river.

This broad terrace above the river confluence was equally attractive 17 centuries later, when Marietta became the first permanent U.S. settlement in the Ohio Country.

After the Revolutionary War, the new American Congress was in financial straits, and unable to pay all the soldiers. A few enterprising New Englanders suggested that cheap land in the West would be a good substitute for cash, and they persuaded Congress to let them form “The Ohio Company of Associates” to broker the deal. Led by Rufus Putnam and Benjamin Tupper, two Brigadier Generals from Massachusetts, and the Reverend Manasseh Cutler, the Company bought a huge tract of land along the Ohio River at a bargain price, then advertised the lots. Enthusiasm for the project ran high among veteran officers; even George Washington, though unable to go, wrote, “No colony in America was ever settled under such favorable auspices.”

In 1788, Putnam himself led the first 48 men down the Ohio River to its confluence with the Muskingum, where U.S. Fort Harmar already stood. The local Delaware and Wyandot Indians were eager to trade, but incursions on their homelands suggested conflict to come. Putnam and the others quickly built the Campus Martius, just outside the ancient enclosure walls, to provide safety for all residents in case of attack. In a nod to their Revolutionary War allies, they named their town “Marietta” in honor of the French queen, Marie Antoinette.

Putnam and his colleagues planned the settlement carefully in relation to the earthworks, and gave them respectful Latinate names: the mound and ring they named “Conus” and around it they developed their own cemetery. One rectangular platform mound became the “Capitolium” and a second, larger one, the “Quadranaou.” The broad ramp down to the river they called the “Sacra Via” – this Sacred Way still suggests solemn processions. Today, a brick monument at the head of the Sacra Via remembers the descendants of those first deed holders, some still in Marietta.

The Marietta settlers established the earliest preservation law west of the Appalachians. To ensure that the earthworks would be kept for public benefit, they appointed a committee to determine, in their words, “the mode of improvement for ornament, and in what manner the ancient works shall be preserved.” While inroads were made on the earthworks over the years, the town’s vigilance has kept some of its main features as stars in its historic crown.

CONUS MOUND

CONUS MOUND

Marietta’s Mound Cemetery is centered on the ancient Conus Mound, with its beautiful ditch and ring. The Conus is a burial structure, probably the best surviving example of the Adena tradition’s large, conical, ringed mounds. It has not been investigated by archaeologists, but the Reverend Manasseh Cutler, one of the town’s founders, wrote this about his early attempt:

An opening being made at the summit of the great mound, there were found the bones of an adult in a horizontal position, covered with a flat stone. Beneath this skeleton were three stones placed vertically at small and different distances, but no bones were discovered. That this venerable monument might not be defaced, the opening was closed without further search.

Cutler’s respectful closing of the mound was typical of the Marietta attitude. By 1837, the town had fenced the cemetery, sewn the monument with grass, and built a stone staircase to the top. All around they had buried their own dead, many of them honored veterans of the American Revolution.

The Conus stands 30 feet tall; its surrounding ditch and ring accent its height and lovely profile. Toward the northwest, the wall and ditch level out to an earth “bridge” – an obvious entryway. A swell in the ground extending from this point once led out to the neighboring square enclosure.

Nearby in the cemetery are memorials to soldiers of the Revolution, and later graves, including that of Benjamin Tupper who once mustered troops for the Civil War at the Quadranaou.

CAPITOLIUM MOUND

CAPITOLIUM MOUND

The large enclosure at Marietta contained four flat-topped, rectangular platform mounds -- an unusual shape for this culture: the so-called Quadranaou Mound with four ramps, the Capitolium Mound with three ramps, another with two ramps, and a final un-ramped mound. The Capitolium still stands on Fifth Street near Washington, near a gateway to the now-lost large enclosure. In 1918, the Capitolium was co-opted as the foundation of the new, Carnegie-funded Washington County Public Library, whose founders insisted this met the criterion of “public benefit,” as specified in the original earthworks preservation ordinance.

One if its three ramps carries the library’s front steps to the sidewalk. Another swells in the narrow yard behind. The best preserved ramp slopes to the alley, on the right side of the building. On the left side, the ancients designed only a kind of hollow between two lobes of earth – archaeologist Bill Pickard calls it an “anti-ramp.”

In 1990, when the library was adding an elevator in the “anti-ramp,” archaeologists were able to confirm that the mound was indeed from the Hopewell era. They also found a hearth, with charcoal from many different kinds of trees – most likely suggesting world-renewal rituals.

QUADRANAOU MOUND

QUADRANAOU MOUND

The largest and grandest of Marietta’s earthworks is the well-preserved Quadranaou. Its vast, rectangular form stands 10 feet tall, and nearly 200 feet long. Elegant, broad ramps climb to the centers of its four sides. Grand gatherings, dances, and games are easily imagined on its level surface. In Civil War times, the Union army used it for mustering recruits. It was also here (or nearby) where one of Marietta’s founders tried a novel method of dating the earthworks. The Reverend Manasseh Cutler recalled:

When I arrived, the ground was in part cleared, but many large trees remained on the walls and mounds. The only possible data for forming any possible conjecture respecting the antiquity of these works, I conceived must be derived from the growth upon them. By the concentric circles, each of which denotes the annual growth, the age of the trees might be ascertained.

Reverend Cutler counted 463 rings on one old stump, but then noticed it was coming out of another, older ancestor – so he doubled the number. It was a good, early effort to use a scientific method – what we now call “dendrochronology.” Little did he know he would have needed to double his number again. His “900 year” figure, though, still appears on some city plaques, instead of reflecting the correct age of 2000 years.

THE SACRA VIA

THE SACRA VIA

Old maps show the Sacra Via as a long, broad ramp with high earthen walls on both sides, leading up from the Muskingum River to Marietta’s large rectangular enclosure. Its monumental scale survives today as a park, a hundred and fifty feet wide. Such grand “graded ways” were often part of Ohio earthwork complexes.

The ramp was carefully engineered: its width crested in the center like a modern highway, its twenty-foot-high walls were lined with clay. This grand thoroughfare would have weathered floods well, and certainly would have impressed visitors arriving at the earthworks by boat. Its central axis is aligned with the winter solstice sunset; a mound probably marked the spot on the cliff top across the river.

Marietta’s first town council made a special resolution to preserve the Sacra Via, in their words, “as common ground…never to be disturbed or defaced.” But by 1882, when J.P. MacLean visited, the walls were gone. He wrote:

On inquiring what had become of these walls I was informed that the material had been moulded into bricks; that a brick-maker had been elected a member of the town council, and he had persuaded the other members to vote to sell him the walls.

The bricks ended up in a Unitarian Church, down the street. Yet even with only hints of its original walls, this ancient roadway is impressive, and the best preserved example of a Hopewell-era “graded way.”

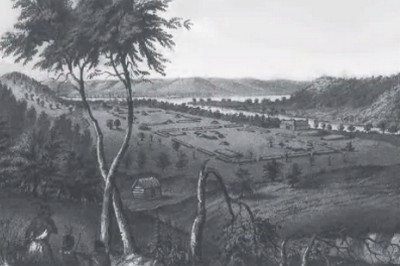

This early illustration of the Sacra Via by Charles Sullivan suggests the grandeur of the walls as they approach the river bank.

HISTORIC HOUSES

HISTORIC HOUSES

Today the town of Marietta is a charming, historic place. The downtown is large, quaint, and thriving; near the riverfront stands a proud old hotel named after General Lafayette, who visited the tiny settlement in 1825, on his grand U.S. Tour.

Up where the ancient earthen walls once stood, wide brick streets are now lined with huge trees, beautiful houses in many nineteenth-century styles, and monumental churches.

The oldest houses in Marietta are in the New England style familiar to the town’s founders, featuring wide fronts, deep sides with chimneys, and sometimes dormers. Several of the oldest houses, like that of David Putnam, are on the “Fort Harmar” side of the Muskingum, reached today by a re-purposed railroad bridge.

Most spectacular of Marietta’s grand houses is “The Castle” – a large, turreted, Gothic Revival mansion, built in 1838 and now open to the public.

FORT HARMAR

FORT HARMAR

After the Revolutionary War, Colonel Josiah Harmar was put in military charge of the Ohio Country for the newly formed nation. One of his first jobs was to keep illegal settlers out while Congress tried to measure and sell off the land. But “squatters” came anyhow, and were aggravating Indian tribes, who had agreed to an earlier peace treaty.

Colonel Harmar ordered a pentagonal stockade fort to be built at the mouth of the Muskingum in 1785, and the officer in charge named it after his commander: Fort Harmar. It may be the only American fort built to protect the Indians from the settlers! Soon afterward though, it actually encouraged white settlement: the new founders of Marietta felt safe in its shadow. The fort is gone, but the old “Harmar” district across the Muskingum retains the name.

The first map of the Marietta earthworks was made by Capt. Jonathan Heart of Fort Harmar in 1787.

TWO MUSEUMS

TWO MUSEUMS

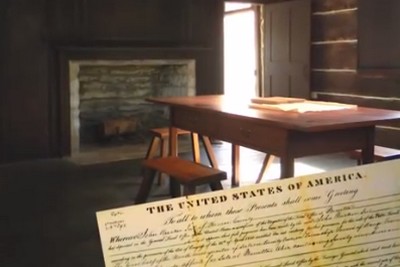

Marietta has two fine historical museums, within 2 blocks of each other. The Campus Martius Museum tells the story of the Ohio Company, and the town’s early settlement and history. It preserves the Land Office where the deeds were signed as new settlers claimed their piece of the “West.” The museum stands on the site of the original “Campus Martius” fortification, and contains one of the original corner houses of that structure, with its sawn and numbered boards, and meticulous pegged joints. Rufus Putnam’s own house also provides a glimpse into the lives of those first settlers.

Nearby on the bank of the Muskingum, the Ohio River Museum is a series of pavilions and bridges, where exhibits tell the story of all kinds of boats and river transport, from dug-out canoes to the largest and finest of the steam-powered riverboats, including their mechanical operation, their pilots, and even their steam whistles. Outside on the water, the W. P. Snyder is also open for visits. In connection with the museum, the annual Sternwheeler Festival, regularly draws 100,000 people to Marietta.

Interior of founder Rufus Putnam’s House, originally part of the Campus Martius fortification, and now open to visitors as part of the Museum.

THE MUSKINGUM RIVER VALLEY

THE MUSKINGUM RIVER VALLEY

From Marietta, a scenic route follows the valley of the Muskingum River through the picturesque historic towns of Stockport and McConnelsville, and on to Zanesville, enroute to Newark or Columbus. (A long but even more scenic alternative is to follow the Ohio River westward to Cincinnati by way of Gallipolis, Portsmouth, and Ripley with its famous Underground Railroad sites, and not missing the beautiful Kentucky towns of Maysville, Washington, and Augusta.)

As part of Ohio’s canal building project in the early 1800s, the Muskingum River was “canalized” by the addition of a series of channels, locks, and dams. The lock mechanisms, designed to be operated by hand, are still functioning. Boats are able to navigate the river today using this same infrastructure, still visible along the riverfronts in Beverly, McConnelsville, and other riverside towns and villages.

In 1896, archaeologist Warren Moorehead and a few aides left the town of Coshocton to survey mounds and earthworks in the Muskingum valley. His notes describe Native sites now lost: pictographs on a large boulder depicting bird tracks and other figures, plus a great face carved in a rock. It’s possible that many markers and symbols once greeted people moving down this river. He investigated the large Sprague Mound then standing, as he noted, “directly in the heart of McConnelsville,” and gave a lecture on his work in the Opera House.

Moorehead’s report suggests the valley had at least 60 mounds, some on the river terraces, some with rings, some high above on bluffs. The locals told him that most of the mounds were places of observation rather than burial, probably much like the grouping at The Plains near Athens, also from the Adena era.

The Opera House where Moorehead spoke is still in use, dominating McConnelsville’s well-preserved, diagonally-oriented town square.

McCONNELSVILLE TO STOCKPORT

McCONNELSVILLE TO STOCKPORT

Far from the major highways, the villages of the Muskingum Valley preserve their early ambience, small local commerce, and fine vernacular architecture. McConnelsville’s diagonal town square is a gem of preservation, surrounded by fine period commercial buildings and houses. The smaller, nearby village of Stockport contains many well-preserved, wood-framed, vernacular houses, as well as the massive, restored Stockport Mill, now an inn with fine dining and lodging overlooking one of the river’s largest waterfalls (1995 Broadway Avenue, 740-559-2822, www.stockportmill.com).

Along a peaceful stretch of riverbank near Stockport, a park and historical marker commemorate the Big Bottom Massacre, where a small band of settlers were killed by Indians. The incident, indicative of the tragic circumstances of the early settlement and displacement process, sparked a wave of military actions against the Native inhabitants of the region.

The main street of Stockport, heading down toward the riverbank and the remodeled Stockport Mill Inn.

NORTH TOWARDS NEWARK

NORTH TOWARDS NEWARK

Follow the river north from Stockport to the historic city of Zanesville, named for Ebenezer Zane who laid out the famous roadway from Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia), to Limestone (now Maysville), Kentucky. The towns of “Zane’s Trace” reflect their early importance along the busy route, and preserve their early character (Lancaster and Chillicothe, for example, besides Zanesville itself).

The most authentic of these early Zane’s Trace settlements is undoubtedly Somerset: the village retains its small, Jeffersonian agrarian scale, and its early courthouse, which faces its Pennsylvania-style town square. Somerset also provides access to the remarkable Glenford Fort Earthwork (see the Flint Ridge, Coshocton, and Somerset itinerary).

The town square and courthouse at Somerset reflect the early settlement patterns of the “Pennsylvania Dutch,” predominantly German immigrants.